by Gunjan Sondhi

Reliance on ‘temporary migrants’ to fill labour market shortages is not a new strategy for Canada. The Temporary Foreigner Workers (TFW) Program has long been criticised and scrutinised by scholars and migrant community supporters. Such programs locate temporary migrants within a precarious legal status and have been seen as creating a racialized underclass. International students, though in this migrant category, have remained invisible in the political and public discourses.

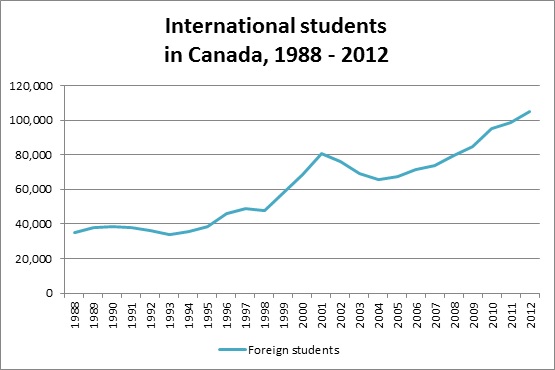

International Student mobility, though not a new phenomenon, has seen growing interest in both policy and scholarly arena across the globe. International students have been an important part of the Canada’s internationalisation strategy. Since the 1950s, this mobility stream and the discussion around the group has ebbed and flowed in reaction to shifting foreign policy agenda.[i] However, over the past decade, Canada has been steadily attracting international students in growing numbers. International Students make up one of the 4 groups within ‘temporary’ migrant category, as opposed to permanent migrants. In 1988, a total of 34,962 international students entered Canada[ii]; in 1997 this number increased to 48,754 students. Only a few years later, 2001, this number doubled to 80,465 international students. Following this sharp increase, there was a decline to international students for the next three years. Then, starting 2003/2004 there has been a rising trend leading to a total of 104810 students entering or re-entering Canada in 2012.

Table A: International Students, annual entry and re-entry into Canada

Source: Citizenship and Immigration Canada, Facts and figures 2012. This table was compiled from using data on Temporary residents by yearly status, 1988-2012.

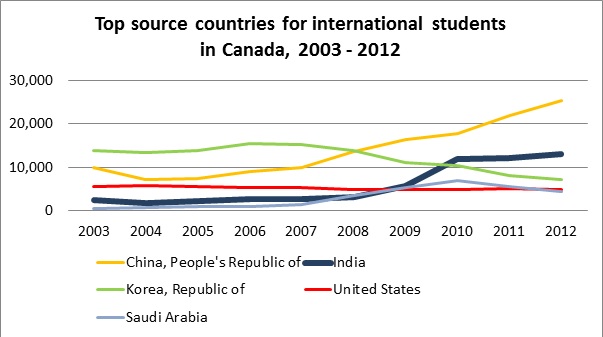

The increase in numbers of foreign students, especially in the past decade, is largely from countries in which Canada has shown strategic interest – China and India. China and India represent the top two source countries for international students studying in Canada. The chart below highlights the shifts in flows from the five source countries between 2003 and 2012. Since 2003, Korea as a source country has moved from first position to now third, behind India. China has usurped the first position amongst the top source countries. The greatest change in student flows has been from India. In 2003, India ranked 5/6 as the top source country of international students; in 2010, India now ranks 2nd, behind China.

In addition to representing its geopolitical and economic interests, Canada’s increasing interest and actions toward recruitment and retention of international students represents the converging of two usually separate policy threads – education and immigration. The long term goals associated with education and immigration have created a particular migration regime with a purpose which extends beyond Canada’s immediate labour market needs. According to Jeffery Reitz, Professor of Sociology,at the University of Toronto, the education goals focus on providing opportunities for the citizens and permanent residents of Canada “to have access to best jobs and enhancing the quality of life”. With regards to immigration, “goals include nation-building, expansion of the economy and population, and the long-term integration of permanent migrants, many of whom are ethnic or racial minorities in Canada.”

Table B: Top source countries of international students in Canada

Source: Citizenship and Immigration Canada, Facts and figures 2012. This table was compiled from using data on Total entries by foreign students by source country.

International students satisfy the needs and requirements of this immigration/education nexus in three ways. Firstly, this group provides an important revenue stream for Canadian universities, colleges and the wider Canadian economy. In 2010, international students enrolled in post-secondary education in Canadian institutions injected $6.3 billion into the Canadian economy. Secondly, Canadian government hopes to fill the demographic and labour market gap through this ‘designer’ migrant group, who will ideally choose to stay and Canada and therefore placing Canada in a privileged position of acquiring ‘bespoke’ citizens. Though how successful this endeavour will be is yet to be seen, as it is too early to tell at this point. Thirdly, as indicated in the Evaluation of International Student Program report, the aim of the Canadian government, with its focus on international student recruitment, is that education in Canada will help individuals integrate faster and better into the Canadian labour market and then as they transition into Permanent residents – into the Canadian society. This ‘path to permanence’ that Canadian government is selling is motivated by the need to reduce the hardships new migrants face when they arrive and settle in Canada, such as – deskilling in labour market, lower wages than ‘native’ born, and social isolation. The winners and losers of this transaction are yet to be discovered.

To this extent, Canada has been pursuing an aggressive strategy to increase recruitment. In 2007, in an effort to increase recruitment of international students, and make itself a strong competitor in the international education sector, Canada introduced its brand Imagine Education in/au Canada. Since its introduction, federal and provincial level actions have been taken to increase recruitment and retention of international students in Canada. In line with this strategy, in 2010, the Canadian government, in collaboration with Association of Canadian Colleges, piloted a program in India called Student Partners Program (SPP). The aim of this program was to streamline the recruitment of international students and flow them directly into colleges. Colleges, in this process, became an extension of Canadian immigration policies, as they became part of the ’immigration’ process to flow students into colleges. This directly benefited the colleges as their enrolment increased. For students, this process was made to look like a streamlined process of immigration into Canada. The introduction of this program lead to doubling the number of international students in Canada from India between 2009 and 2010, as show in Table B above.

In a recent recommendation of a task force, it was suggested that Canadian government and universities should continue to increase recruitment to “nearly double the number of international students from 239,000 in 2011 to 450,000 by 2022.” This is total number of ‘temporary migrants’ in Canada with the status of international students; and not just new entries or re-entries.

For the Canadian government the international student program is a means to “maximize their (students’) contribution to Canada’s economic, social and cultural development while protecting the health, safety and security of Canadians”. The health, safety and security of the students is not under consideration in this program. Also, the benefit to international students is also not visible in the policy discourse. Until now, the wellbeing and experiences of international students has remained largely invisible. This is not surprising. Taking a look at the history of Canadian temporary migrants programs – most recently the TFW, the impact of these programs/policies on migrants themselves are rarely acknowledged at the macro level. It is only through efforts of community grassroots organisations, activists and scholars who have brought to light the challenges of everyday life faced by temporary migrants. Work of Luin Goldring, Carolina Berinstein and Juidth K. Bernhard, on institutionalization of precarious migratory status is key to problematising and theorising the impact of transitioning from temporary migrant status to permanent resident status. Goldring and Landolt discuss the challenges and struggles temporary foreign workers face due to their precarious legal status – particularly when their economic outcomes are examined. In this key work, they also highlight the role of changing legal status – from temporary migrant to permanent- to show that the initial period of stay as temporary migrant has a negative impact on the future economic outcomes of the migrants.

With this in mind, If the goal of Canadian government is to attract international students to generate a stream of bespoke migrants to convert into designer citizens, it is imperative that the precarious status of international students is acknowledged since that status will shape the experiences of students in Canada. These experiences in turn will greatly impact their future in Canada, just as it has for other ‘temporary migrants’ – and determine their degree of success compared to other temporary migrants, permanent migrants, and those who are ‘native’ born.

Gunjan Sondhi recently received her PhD from University of Sussex. Her research focuses on issues of International Student Mobility, gender and class. At present, she is based as a resident affiliate at CERIS, York University, Toronto.

[i] See Trilokekar & Kizilbash 2013 for a brief history of international students in Canada.

[ii] Initial entry and re-entry

Very provocative, timely and excellent article. My only quibble is that (if I recall correctly) Goldring and Landot’s research focused more on precarious workers and so I wonder if their findings would really be transferable to international students who come to Canada for the purposes of education rather than employment.

LikeLike

Thanks for the comment Sarah. You are correct that the focus of Goldring and Landolt’s study is precarious workers. I want to extend the concept of precarious legal status – that which makes temporary migrant workers ‘precarious’ – to international students. By thinking of international students as possessing ‘precarious legal status’, we can begin to foresee some of the challenges this group of migrants are likely to face, based on experiences of Temporary Foreign Workers and other temporary migrants in Canada.

LikeLike